Exploring the Patient Voice—in Two Words

Asking patients to describe their thoughts and feelings about their cancer and treatment using just two words can be a powerful tool for capturing the essence of their experience. Specific words have the unique ability to convey deep emotions and significant aspects of a person's journey, often revealing insights about their challenges, fears, and hopes that are difficult to obtain through structured surveys.

This approach is valuable because it honours the patient's perspective, supporting patients to feel heard and validated. Listening to and incorporating patients' perspectives enables us to design adherence strategies that are not only more relevant but also more impactful, fostering stronger connections between patients and the support they receive.

Asking patients to describe their thoughts and feelings about their cancer and treatment using just two words can be a powerful tool for capturing the essence of their experience. Specific words have the unique ability to convey deep emotions and significant aspects of a person's journey, often revealing insights about their challenges, fears, and hopes that are difficult to obtain through structured surveys.

This approach is valuable because it honours the patient's perspective, supporting patients to feel heard and validated. Listening to and incorporating patients' perspectives enables us to design adherence strategies that are not only more relevant but also more impactful, fostering stronger connections between patients and the support they receive.

Methodology

We conducted a global online survey with 126 cancer patients who are taking self-administered anti-cancer medication at home.*

In addition to completing a range of psychometrically-validated questionnaires to explore the patient perspective, participants were asked to use two words to describe their cancer, and two words to describe their treatment.

We were interested in exploring patient representations of their experience, and the nature of the responses, to discover new insights that might not be uncovered by a set of standardised questionnaires.

*More information on the demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample can be found here.

Rates of Nonadherence

Using the psychometrically validated five-item Medication Adherence Rating Scale1, 56% of the sample reported at least some degree of nonadherence to their anti-cancer, at-home medication.

This is comparable to levels found by WHO and other published studies.

We analysed the patient responses between these two groups.

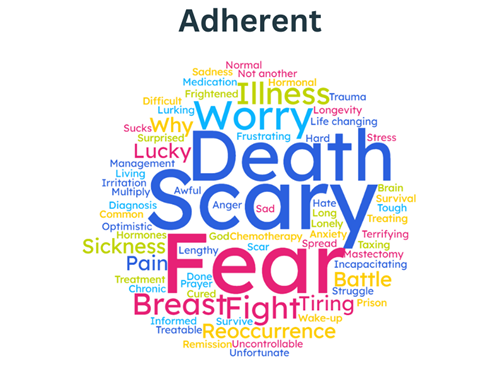

In the Patient’s Words: Thinking About Cancer

Participants were asked:

"When you think about your cancer, what two words come to mind?"

This question taps into a person's immediate emotional or cognitive response to their condition, providing insight into how they conceptualise their illness.

Emotional Experience & Impact of Cancer

The most frequently cited words in both groups were those relating to emotional experiences, with common words including fear, anxiety, and scary. Sadness, anger, and shock also appeared prominently. There were no noticeable differences in the frequency or other type of emotions expressed between participants who fully adhered to their treatment and those who showed some level of nonadherence.

Words describing the physical impact of cancer were also frequently mentioned. Nonadherent participants used these terms three times more often than adherent participants. Commonly reported terms among the nonadherent group included pain, exhaustion, and fatigue.

Beyond the physical impact of cancer, participants also reported a significant impact on their quality of life. Nearly two-thirds of those describing a negative impact on their overall quality of life also reported some degree of nonadherence. Words such as life-changing, stress, and "sucks" were frequently cited.

Overall, nonadherent participants were more likely to use language reflecting both the physical and overall negative impact of cancer on their quality of life compared to adherent patients.

This may suggest a tendency towards a more negative perspective and / or a worse experience with symptoms and effects associated with cancer and its treatment.

Nonadherent participants were also less likely to use words referring to the timeline or progression of cancer suggesting that they may be less well prepared to deal with the long timelines typically associated with cancer treatments.

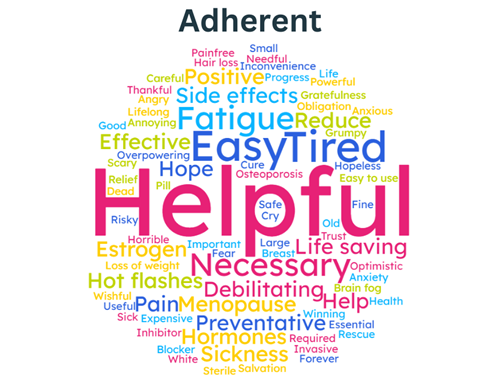

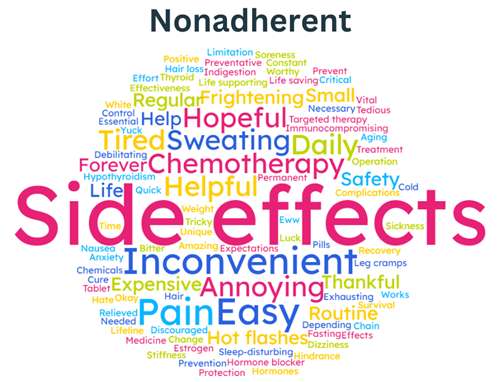

In the Patient’s Words: Thinking About Treatment

Participants were asked:

"When you think about your main cancer medication, what two words come to mind?"

This question taps into a person's immediate emotional or cognitive response to their medication, revealing their views on its impact or significance in their treatment.

Side Effects, Treatment Burden & Medical Focus

Side effects were the most frequently mentioned treatment-related words. Participants referred to them in both general terms (e.g., side effects, complications) and in more specific terms, with fatigue, pain, and hormonal side effects (e.g., hot flashes, menopause, sweating) being the most cited.

Notably, nonadherent participants mentioned side effects nearly twice as often as adherent participants, suggesting that side effects are more top of mind for nonadherent patients. This could indicate that they experience these symptoms more frequently or are more vigilant about their potential occurrence. This finding aligns with an earlier published finding from this research that found that nonadherent patients perceive they are more sensitive to medicines than adherent patients. More information on this finding can be found here.

Nonadherent participants made more frequent reference to the routine of taking treatment, using words such as constant, daily, and regularity. Nonadherent participants were also more likely than adherent participants to reference the burden of taking treatment, using words such as inconvenient, tedious, and effort.

An additional interesting difference between adherent and nonadherent participants was the use of medically-focussed words. Nonadherent participants more frequently described treatment directly, in very tangible ways, using words such as treatment, medicine, and chemotherapy. Nonadherent participants were also more likely to describe the physical attributes of the treatment, such as its size (e.g., large, small), form (e.g., pill, tablet) and colour (e.g., white, brown).

There was a trend among adherent participants to more frequently describe treatment with reference to the body, such as citing the location of the cancer (e.g., breast, thyroid), or the action of the treatment (e.g., hormone, inhibitor). This could indicate that adherent patients have a broader perspective on their treatment than nonadherent participants, seeing it as acting on the body and the cancer experience.

Implications for Intervention

Overall, we found that nonadherent participants focussed more on treatment side effects and burdens, as well as the physical aspects, whereas adherent participants were likely to have a more integrated perspective.

Interventions should aim to help nonadherent patients reframe negative aspects and connect more deeply with their treatment to see it as actively supporting their health journey.

By understanding these differences in language, we can refine the content and framing of support interventions to better align with patients' experiences and needs.

Optimising Oncology Patient Support

Our findings reveal new insights into why people living with cancer might choose to not take their at-home anti-cancer medication as prescribed. They demonstrate the need to provide targeted and personalised patient support for those with cancer.

As part of oncology patient support programmes, interventions are required that specifically address the individual's key reasons for nonadherence. Optimising oncology patient support programmes this way will enable and empower those living with cancer to Change for Good

To learn more about how our findings can be leveraged in your patient engagement strategy, contact our Global Head of Behavioural Science and Lead Researcher—Dr Kate Perry—for a 30-minute online discussion: Click Here to contact Kate and request a meeting and receive a free copy of our study report.

Read about our expertise and more behavioural science insights.

References

1. Chan, A. H. Y., Horne, R., Hankins, M., & Chisari, C. (2020). The Medication Adherence Report Scale: A measurement tool for eliciting patients’ reports of nonadherence. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 86(7), 1281-1288. doi:10.1111/bcp.14193